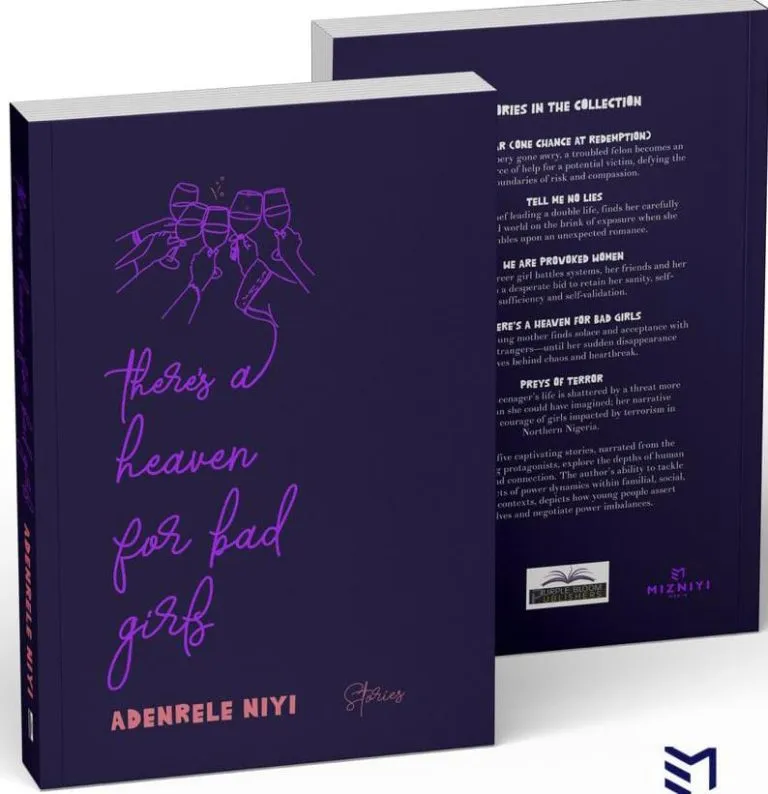

It is the shorthand of prose fiction, the short story form. Its charm lies in its brevity to compress what a full length novel could do in very few words. Mastery of the short fiction or short story is an art of its own that requires some level of talent and discipline to accomplish. Although they are just five short stories, There’s a Heaven for Bad Girls is a short story collection that accomplishes much even in its brevity. Unusually, Adenrele Niyi introduces chapters to her short stories. Imagine short stories also having chapters! That’s the ingenuity and charm that Niyi brings to bear on her stories which make them feel extended beyond their usual short lifespan.

From “O’Car” (One Chance at Redemption), “We Are Provoked Women,” “Tell Me No Lies,” “Preys of Terror” and the title story, Niyi leaves no one in doubt what she intends to accomplish – tell real life stories of Lagosians and that occasional girls’ story in far-flung insurgency-ravaged part of the country. But she starts with the familiar Lagos stories, of thieves who use the ubiquitous Lagos’ danfo as smokescreen to rob unsuspecting passengers. There are four of them – Tiny, Ejiro, Major and Lateef – versed in the art of using a Lagos’ yellow bus to rob commuters. But on this fateful day luck runs out on them or indeed the supernatural intervenes. They pick up a pregnant woman with other passengers. There’s a tire blow-out on the way and they are stranded. Just then the pregnant woman goes into labour – the near-death experience triggers onrush of birth pangs. The robbers are in shock. What’s worse, a police van stops to give assistance; the police pick up the pregnant woman with one of the robbers in tow. The robber is carrying an unlicensed pistol and they drive off to the nearest hospital.

The second story “Tell Me No Lies” is uniquely told. In it you find all the inflexions of millenia lingo, a quaint colloquial usage that’s pleasing to the ears. Kanyin is a Lagos young woman who’s trying to make a life in the food vending business. Her ofada rice is the rave. Kwame, a Ghanaian guy, just discovers ofada rice when he tastes Kanyin’s at a party. At his office party two weeks later, Kanyin is the caterer, but it’s also a pretext to meet up with the amazing chef. But that evening turns out to be Kanyin’s unravelling. Right there in Kwame’s arms, Kanyin takes ill, and he rushes her to his clinic. Kwame is the right guy in all the right places; she has almost called it quits with her married lover who rented her an apartment. But it seems her first night with Kwame is in ruins. When the doctor steps in to inform Kanyin what is wrong in the presence of her twin brother, it’s the last, devastating news she expects. How does she tell Kwame? Only tears well up from repressed emotions and the ruination that stars her in the face.

The third story “We Are Provoked Women” has its peculiar charm. It’s about being a Nigerian and Lagosian. Someone said somewhere that being a Nigerian is a full time job, and being a Lagosian is another side hustle added to the full time job. You will not agree less when you read this story. Here, Niyi fleshes out what it takes to be Nigerian, particularly a young Nigerian woman who just wants to get ahead of the pack. Rolake does not have a problem with her job; one of the lucky few, you’d say. But the basic dynamics of living as a young person and Nigerian are daunting and enough to break the lion-hearted. Her parents, particularly her father, believe she’s old enough to bring home a man to marry. How does she explain to him that marriage and all its baggage are far from her mind?

Rolake’s friend is due to wed in London in a few weeks; it will be her first trip outside Nigeria. Rolake is excited at the prospect, but she is denied a visa; her Nigerian passport is the unfortunate albatross. This tragedy sits heavy in the pit of her stomach, so much so that she cuts off from her friends and wallows in depression. What’s more galling is that she does not have the right political or business connection to change the unfortunate situation. It’s only through the help of a psychologist and her French boyfriend that Rolake will turn a bend. As a young woman with a forceful character, a Lagos-goal-getter, who wants to be in control at all times, Rolake is almost broken by the visa denial. It’s as though her world is coming to an end. As her self-belief is punctured by an adversary beyond her control, she’s utterly shattered.

“Preys of Terror” is the fifth story that makes up this slim but important collection. The insurgency in the northeast is no longer news. How they abduct schoolgirls into their dens as wives is no longer news either. But how do these girls, or some of them, square up to these predators and survive and even vanquish them are the stuff that pepper Niyi’s story. It’s the story of Jamal the predator and Hassana, supposedly the prey. These two antagonists circle each other in their peripheral vision, with Jamal regarding Hassana as the victim who will fall into his vicious clutches while Hassana sees Jamal, as a conquerable brute male. They size each other up in the manner of the hunter and the hunted. Who blinks first!

In There’s a Heaven for Bad Girls, Niyi has painted an admirable canvas of characters and worlds, as she fleshes out depths of emotions. Among the bus robbers, Tiny still manages to retain his humanity; he remembers how his own mother died in pregnancy while he made vain efforts to soothe her pains while his father was at work. As the other passengers remain helpless, it’s Tiny who rallies the pregnant woman and gives her succour. And when the pregnant woman clings to him for comfort, as the police van speeds her off to hospital, Tiny does not shrug her off in spite of the danger it poses to him and his gang. Tiny is still capable of human feelings in spite of his peculiar job. Rolake is the typical Lagos girl – all ambition and can-do spirit. But a setback shatters all that hardcore and what is revealed is just another girl next door, as vulnerable as they come. Her story also highlights the Nigerian peculiar dilemma. What does it mean to be a holder of the Nigerian passport? But it’s precisely why you’re a Nigerian, right? It’s a job, remember? You improvise and forge ahead regardless. That’s what you do on the job. Kanayin is caught in the web of a relationship she wants to leave behind for the promise of a new, better one. How does she navigate this delicate situation and still keep her sanity?

In the stories “O’Car,” “Tell me No Lies” and “Preys of Terror,” Niyi leaves a margin of metaphorical error, so to say. She allows her readers to continue writing the stories, in their heads or minds. She doesn’t put a final end to the stories, because she believes the reader should be equally invested in the stories, and so should end them whichever way they like them to end. It’s a creative trick of getting readers involved, and Niyi succeeds superbly in getting her readers sucked into the bowels of her writing project. In these stories, Niyi therefore invites her readers to be co-creators of her fictional world and characters.