I.

Out of a ship docked in Augusta, a town in southeast Italy, immigrants emerge from different parts of the world. The writer Teju Cole is allowed to see them, to ask a few questions for a project he’s working on. When he meets a pair of couples, he lingers. All four are Nigerian, and just before the immigration officials take them away, Cole, who’s previously written about being agnostic, says: “You’re welcome. God be with you.”

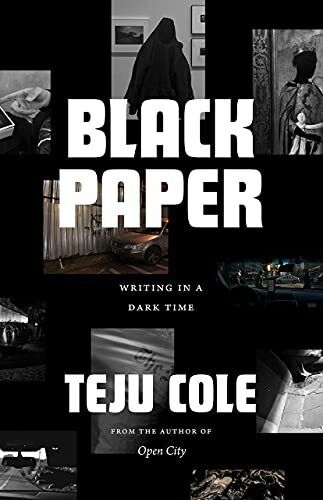

This is a scene from his latest book, Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time, a collection of essays that bursts with unrestrained humanity. It complements the analytical poise of his first collection, 2016’s Known and Strange Things. Here, Cole’s subjects are immersed autobiographically, varied in scope but thematically linked by his consideration of life’s double agents: light and darkness—the latter more frequently. This is explored throughout the book’s five sections: “After Caravaggio,” “Elegies,” “Shadows,” “Coming to Our Senses,” and “In a Dark Time.”

Cole investigates the space between modern states and the people who pass through the states. Immigration is his central concern, and its reasons make up the “dark time” of this book’s subtitle: wars, poverty, widespread hunger, the dearth of culture, crippled democracies. In his trademark style, there’s an assortment of angles from which he creates complex, credible views. Photography is often his most beloved vantage point, his camera a portal to deeper streams of consciousness.

In “What Does It Mean to Look at This,” he observes the “intersection of violence and photography.” He reaches for influential artists in the field—Susan Sontag, most notably—and tussles with their ideas on the meaning of taking a photograph, especially those of oppressed people. Is the world perfect enough to rely on sympathy? Are images powerful enough? Cole has his own opinion, but, in the conversational throb of his work, he pulls in the philosophies of more contemporary critics like Ariella Azoulay and Susie Linfield, arriving at a less clear-cut position. His reading of Susan Meiselas’s stirring photograph of five people in Esteli, Nicaragua, holding their noses against the smell of burning flesh, leads to his final proposition of the functions of photography. “Taking photographs is sometimes a terrible thing to do,” he writes, “but often, not taking the necessary photo, not bearing witness, or not being allowed to do so can be worse.”

There: bearing witness—the primary inspiration behind Cole’s movements. It is not so much about passing an opinion as it is about being there, about simply saying: I see this. I see it for what it is.

Few essays in Black Paper illustrate this better than “Passages North.” He visits Norway, arriving at Oslo and Utøya, a small island nearby, where in 2011 a local terrorist killed over 77 people, detonating a car bomb in the capital city and opening fire on inhabitants, mostly killing members of the youth group of a political party he hated. Cole doesn’t consider man’s confusing penchant for evil as much as he colors the small, quiet lives of the neighborhood people, and the hues sadness has assumed in their everyday existence. His lucid tone mirrors the serenity of the Scandinavian landscape. “Art is the remembrance of the details,” someone says, “those details you can’t possibly remember.” Cole notes this.

How important is it to remember? If, according to Cole, “each culture represents specific instances of sensitivity,” then those of Africa are especially sensitive. We remember our dead and they remember us, their stories shifting as light, illuminating our futures. In “Mama’s Shroud,” he tenderly rouses the life and spirit of Abusatu, his grandmother who was born in 1928 and died in 2017. The piece begins with a simple gesture: he seeks photographs of her. “To remain close to our dead, we cherish images of them,” he writes. “Photographs are there after people pass away, serving both as reservoirs of memory and as talismans for mourning.”

“Two Elegies,” written in memory of the art curators Bisi Silva and Okwui Enwezor, begins with a dream and offers a dreamlike sequence of events, bobbing across memory and time like a ball on water. He invokes the Yoruba saying, K’ ójó pé si’ ra: a prayer that bereavements, although imminent, be spaced out mercifully. A defiant, tender streak continues with his quoting of Anne Carson: “You remember too much, my mother said to me recently. Why hold on to all that? And I said, Where can I put it down?”

In “Four Elegies,” he pairs the music of Aretha Franklin, the Malian Mande master Kassé Mady Diabaté, the Chinese American architect I. M. Pei, and the Nobel Prize laureate Tomas Transtromer, whose poems give “the sense of being pulled along by forces external to yourself.” His connection to these artists is, however, technical.

He strikes closer to heartbroken in his letter to John Berger, where he tells his departed friend a story, of Milo, a boy who loses his sight but has “a memory map of the house plan” and whose guardian has “feathers to the corners and legs of the furniture so that he collides with hard edges less frequently.” He quotes a Berger passage, about how “Life depends upon finding cover.” Berger’s art, he writes, is “like feathers you’ve thoughtfully placed in the places where we meet.”

II.

Influenced by his training as a photographer and art critic, Cole’s writing reaches into multiple pockets. He follows other creators as eagerly as he creates. In Black Paper, these appraisals show in the third section “Shadows.” He writes on the South African photographer Santu Mofokeng, who created iconic images during Apartheid, and on Lorna Simpson, whose work is “about the ‘neutral’ space of ideas and the particularized experience of the body.” Of the painter Kerry James Marshall, he writes: “Timeliness is being in time and on time. Work conversant with the history of art, and in conversation with it, is timely”—a sort of manifesto for Cole’s own work.

Cole offers an “incantation” for Marie Cosindas, whose photographs hold “such potency that they seem magical, dependent on something beyond mere sleight of hand for their mesmerizing effects and unified mood, so that the experience of looking at a selection of them is like watching a single sentence unfurl over several pages, driven along by an invisible inner consistency.” This essay is then delivered in a single sentence, reputed for being the longest ever published in The New York Times.

In such essays, Cole revels in the traditions of his separate practices. “The Blackness of the Panther” begins with a rumination on his Blackness (Is he Black, Yoruba, or African?) before segueing into a struggle to remember the big cats that fascinated him as a kid, and then it became an assessment of Blackness in Western media, a criticism of the implicit commentary of films like Black Panther and Welcome to America. “Wakanda is a monarchy, and so is Zamunda,” he notes. “Why are monarchies the narrative default? Can we dream beyond royalty?”

In the same essay, while he pondered the cats, Cole worries about contemporary speed, how easily he could get an answer with a few clicks. “Knowledge,” he writes, “in the days before instantaneous electronic recall, was full of potential energy. It was attended by a guesswork that fostered a different way of knowing, one that allowed for ranges rather than insisting on points.”

It’s obvious that Cole does not buy the illusion of certainty. In “Epiphany,” he praises James Joyce’s Dubliners and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man as books with “heightened sensation and flashes of insight.” He quotes lengthily from his own debut novel, Open City, to show the framework through which its narrator Julius is conceived. He endorses one of his influences, the German author W. G. Sebald, for his “intense, emotionally charged but intellectually unflagging approach” in “entire books that are almost nothing but the headiness of an associative dream.” Other books he places in this conversation are Toni Morisson’s Jazz, Orhan Pamuk’s Istanbul, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, all of them “texts of sensorial muchness.”

III.

The essays in Black Paper, like all of Cole’s writing, are suffused with poetic influences. They build their own inner rhythms and sometimes abandon them. “A Quartet for Edward Said” and “Ethics” are pieces with elaborate movements. The former creates a magnetic, elegant, and critical portrait of the influential scholar and writer; and in the latter, a touchstone of Cole’s craft is revealed: seeing. “These are the reasons I travel, or read, or look at art: to find out, to feel, to tremble, to forestall any risk that the active fact might be rendered passive or useless,” he writes. “I open myself up to shake off ‘raising awareness’ and take on ‘bearing witness,’ to go closer, to feel what I feel there (wherever ‘there’ may be).”

In the book’s opening piece, “After Carravagio,” Cole had delivered on this ethos. It is a winding exploration of the 16th century Italian painter, the “quintessential uncontrollable artist” who perfected the chiaroscuro technique which pairs “harsh light with deep dark.” Cole’s journey through Italy, led by Caravaggio’s past, opens a wider conversation into art, the politics of art, Italian philosophy, Blackness, and the patterns of migration.

Cole views the paintings of Caravaggio and offers informed readings of them, but his concern lies in their constant depiction of horror. “Why did he paint so many martyrdoms and beheadings?” he asks. Earlier, a taxi driver mistakes him for a footballer, and he replies that he’s here to view paintings of Caravaggio. Unconvinced, the driver lets the conversation go. “Indeed, what else could a young African going to a hotel be?” reasons Cole, with only the slightest hint of sarcasm.

Writers like Cole probe the secret histories of things. The freewheeling vision of Black Paper is akin to those of Sadiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, Geoff Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage, Manthia Diawara’s In Search of Africa, and, of course, the compassionate travelogue-memoir-criticism books of John Berger. His walk through Italy takes the unpredictable mode of fiction, finely wrought to inspire curiosity in the reader. In one scene, he views a painting, The Burial of St Lucy, with a stranger, the refugee son of a Gambian politician. Facing Caravaggio’s The Raising of Lazarus and Adoration of the Shepherds, he’s left “awestruck, out of breath and caught between these two immensities,” leading to a profound reflection on the power of art:

It can also often be wonderful, giving the viewer a chance to be blessed by a stranger’s ingenuity or insight. But rarely, something even better happens: a painting made by someone in a distant country hundreds of years ago, an artist’s careful attention and turbulent experience sedimented onto a stretched canvas, leaps out of the past to call you—to call you—to attention in the present, to drive you to confusion by drawing from you both a sense of alarm and a feeling of consolation, to bring you to an awareness of your own self in the act of experiencing something that is well beyond the grasp of language, something that you wouldn’t wish to live without.

And yet Black Paper is not a book of only calm. In “Resist, Refuse,” Cole urges action from every citizen of the world—reminiscent of the lessons in Khalil Gibran’s The Prophet. He proposes “a resistance made of refusals”:

Refuse the conventional arena and take the fight elsewhere. Refuse to eat with the enemy, refuse to feed the enemy. Refuse to participate in the logic of the crisis, refuse to be reactive to its provocations…Refuse to ignore the plight of the imprisoned, the tortured and the deported. Refuse to be mesmerized by shows of power. Refuse the mob. Refuse to play, refuse decorum, refuse accusation, refuse distraction, which is a tolerance of death-dealing by another name. And when told you can’t refuse, refuse that, too.

Cole’s eighth book is technically excellent, and more importantly, it blazes a wholesome style to living and being alive. It holds many truths, some conflicting, because this is what humanity is.

Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time is published by the University of Chicago Press.