- Echezonachukwu Nduka

- March 16, 2023

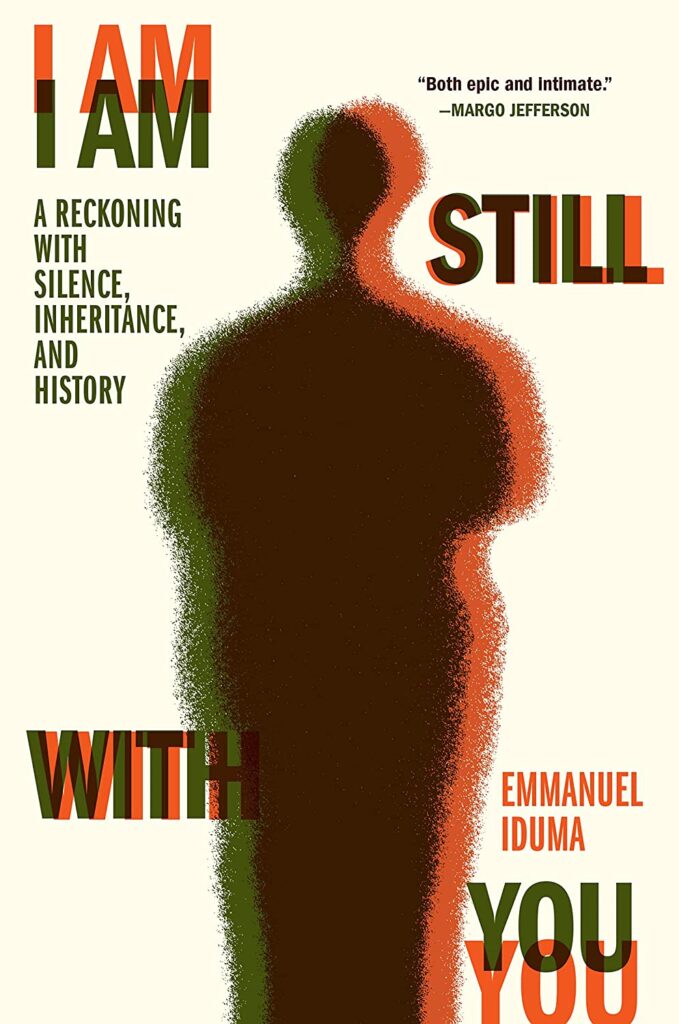

I Am Still with You by Emmanuel Iduma, Reviewed: Haunting Histories

The essayist and novelist Emmanuel Iduma is named after his uncle who left home during the Nigerian Civil War, in 1967, to fight on Biafra’s side, but never returned. Decades later, Iduma travelled from New York to his hometown of Afikpo, Ebonyi State, southeastern Nigeria, in search of closure. “To return is to be recognized,” he writes in his new memoir I Am Still with You, “and this is what I sought during my visit now to Afikpo — to be recognized, in some way, as the heir to my uncle’s life.” But how does one search for truths documented mostly in memories, recollections, and fragmented narratives?

To contextualize his work, Iduma presents a rather peripheral history of his Igbo people, traced back to the Nri hegemony and the Aro Empire. He interweaves the stories of both his late uncle and his late father with those of three major Igbo figures whose destinies were tied to the war: the poet Christopher Okigbo, the Biafran leader Odumegwu Ojukwu, and Major Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu, one of the leaders of the country’s first military coup, which set off the chain of events that culminated in the war. (In Okigbo’s hometown, Ojoto, Iduma seeks the river which inspired Okigbo’s famous poem “The Passage.” He is surprised when no one knows any “Idoto River”; instead they show him a stream called Mmiri John.)

Here, the narratives are fragmented, not linear. Their style and tone suggest that the author is in search of prized information and needs answers urgently. Think of a person who dashes into a room, goes this way and that way, opening different boxes and drawers simultaneously. Yet the story flows. The juxtaposition serves a purpose: while his uncle’s departure is akin to Okigbo’s, with pain for their families, Ojukwu’s return from post-war exile is to pomp.

Iduma takes us to Nsukka, seeking access to the library of the University of Nigeria, where publications on Biafra are abundant but carefully restrained. In Onitsha, we meet his foster parents, who raised him and his siblings when their father, Rev. Francis Agbi Iduma, was away for studies in the US. What stands out here is how silence has become a coping mechanism for the generation directly affected by the war. “They inherited, most acutely, an ability to transmute trauma into unvoiced questions,” writes Iduma.

Iduma is self-aware, has an eye for the quotidian, and the empathy to make connections and meanings. He writes about his family with fondness. When his stepmother weeps at his younger sister’s wedding, we find grief and joy intertwined. In measured prose, he ruminates about his father’s final moments: “Everyone alive has been touched by death. But what of those who have passed from this life, what are they touched by? Love? How does love reach from one state of existence to another?”

Grief is a communal language of the living. Iduma sometimes seems to ask: what do the lives of others teach us about ourselves? There is something unnerving about the vagaries of memory, as demonstrated by the respondents, extended family members in fact, who had conflicting recollections of what his lost uncle looked like. Was he truly dark or fair?

Since no photos of his uncle survived the war, Iduma estimates his facial features based on those of his surviving siblings who took photos after the war. To deal with the limitations of memory, one has no choice than to be speculative. It is the ultimate coping mechanism, an act of survival. Many people disappeared during the war. Their survivors today are dealing with the sting of that reality. Will they ever find closure? (Iduma makes reference to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun, in which the character Kainene disappears.)

In most of his travels — Ahiara, Uli, Enugu, Umuahia, Aba — people he is scheduled to meet back off without notice. Members of the Indigenous Peoples of Biafra (IPOB) show distrust and apprehension towards him. Why does he want to know about Biafra at a time when IPOB members are being persecuted? Is he a spy? It does not help that his spoken Igbo is inadequate. “And so how long will the agitation for Biafra last?” he asks about the movement.

Notable in his conversations with his wife, the novelist Ayobami Adebayo, is the feeling that people do not have to experience war firsthand to be affected by it. The possibility of experiencing trauma without memory is lost on those who wonder why young people born many years after the war are agitating for the actualization of the defunct state.

A lawyer and art critic, Iduma’s curiosity and brilliance shine when he writes on the intersection of images and texts. His interventions show a knowledge of semiotics, and he brings emotional maturity to bear. Teju Cole, whose writing and photography Iduma cites as an influence, once said this about literary echo: “Echo is very important to me. I love the repetition of motifs, or the slight alteration of what’s been said before. This is part of how one creates a mood, a psychological caul, in fact, around the reader.” I Am Still with You is filled with such echo of loss, of longing, so much that before you are halfway in, the mood envelopes you. It takes skill to deploy this in a way that is not easily seen on-page but is instead felt.

I Am Still with You takes its title from Psalm 139, Verse 18. But it could also refer to the meaning of the author and his uncle’s name “Emmanuel” — the sempiternal presence of God. Or how the ghost of Biafra is still with Nigeria, yearning for truth, for justice, for closure. (The violence is certainly with Nigeria, which Iduma skirts in the book’s opening chapter through his personal account of the EndSARS protests in Lagos.) For readers, the title might as well be a compelling gesture to family, to his wife Adebayo’s debut novel title Stay with Me — to which Iduma has now replied with a reaffirming memoir of love: I Am Still with You.

Yet unlike in the present, the past in the book has no answers that can be enough.